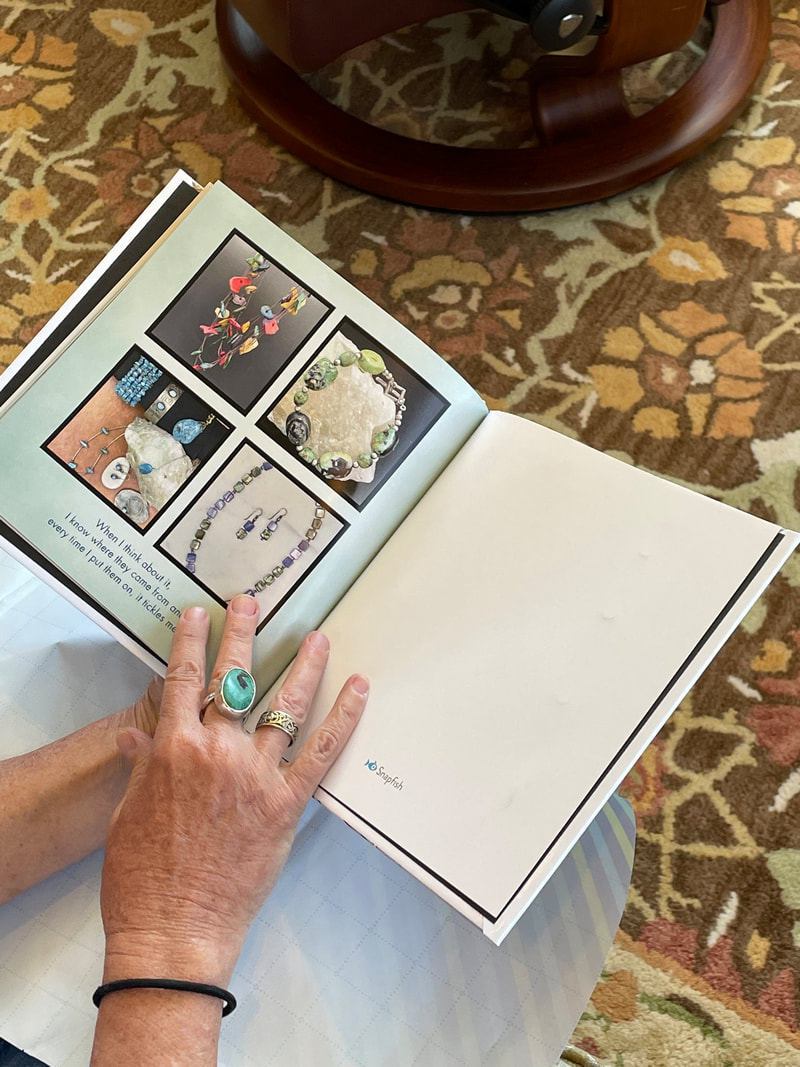

Picture yourself mingling at a social gathering. Which would you find less intimidating to be asked by a stranger?“Tell me a story about your boss at your last job?” OR “Where did you get that cool necklace?” I think the necklace approach is less threatening, and could just yield the more intimate conversation. If you asked me about the shiny necklace that I had chosen to wear for the occasion, I could tell you about my relationship with my delightful mother-in-law who gave it to me. That might lead me to the occasion I received it, and I might even tell you why I wore it tonight. That is a lot of context! As personal historians, when we tune into something that is important to our clients, we have a chance to hear their deeply held values as they relate to uniquely personal treasures in their lives. Humans love shiny objects. We all seem to have a special collection of something. What do you collect, either intentionally or unintentionally?

Q: Why do we hold on to these old things? A: Because these artifacts say something about us when we say something about them. Sometimes we don’t even realize we have a collection until someone notices all our little bowls and then asks us what that is all about. Who can resist being seen, noticed, listened to? I am a big fan of the art and the value of asking questions, but after raising two sons and working as a mental health counselor with reluctant children, I have come to appreciate a more oblique approach to information gathering. I like to know what motivates people, and it is fun to listen for clues about that in conversations on the air, in the clinic, or on the patio. I wondered what would happen if I recorded people talking about the things they love? What if we focused more on memories and reflections than on telling stories with beginnings, middles and ends? Would there still be juicy content? The short answer is YES. The stories just come tumbling out. For some people, talking about the things they love is just way easier than telling a “story. Our thumbprints are all over the items we have collected and saved over the years. Maybe our loved ones don’t want our treasures, but these treasures can be a tool for connecting us to one another. Photographing a collection and making audio recordings of people sharing their favorite things conveys a sense of tempo, feeling, and personality that goes along with the collection. This is the stuff that bonds us to one another. And as my most recent client said, “Sometimes it's deeper than you think, talking about where a piece came from, or what it means to you.” If you are working with someone who seems a bit guarded when you ask direct questions about their lives, try talking with them about their stuff —the stuff of life.  Kate Manahan is a radio producer/host and oral historian who founded Thumbprint Audio in late 2020. Her new personal history business records family and individual narratives, sometimes represented in client-narrated picture books. Kate lives and works in Kennebunk, ME and collects rocks, old political buttons, and—as it turns out—things with images of birds on them. www.thumbprintaudio.com [email protected] 207 604 9015

0 Comments

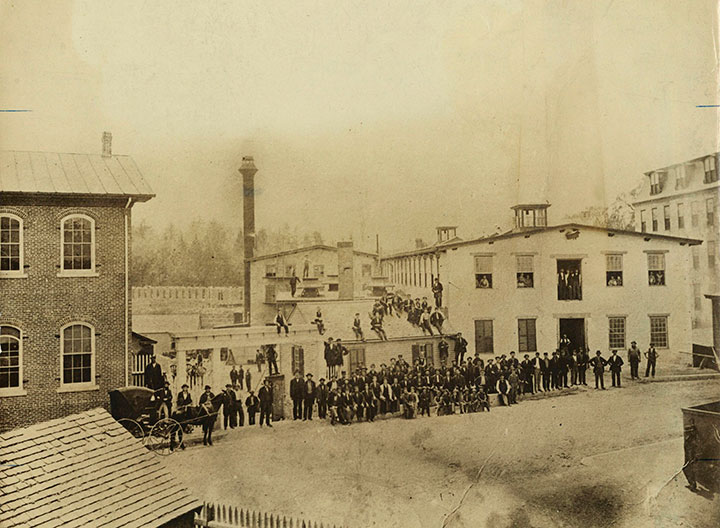

By Abigail Epplett While taking a “Museum & Digital Technology” class at Tufts University last fall, I was tasked with creating a system that utilized new technology and was beneficial to an organization in my community. I live in the Blackstone River Valley, a national park with a rich history whose story has not been fully told. I began thinking about the difficulties of collecting the oral histories of lifelong residents and being able to share them with the public. I realized that I could create an easy-to use interface that would allow personal historians to gather stories from millworkers using their computer or mobile device, along with spreading the stories online or through social media. (You can look at the process here.) The Blackstone River Valley has a long history as the “Birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution.” At the southern end of the valley, Slater’s Mill in Pawtucket, RI became the first water-powered mill in the United States in 1793. From then on, hundreds of mills in all shapes and sizes were built on the Blackstone River and its tributaries. Local people left their farms to work in the mills, while immigrants came from Europe and Canada to run the machines. Amazingly, this millworker lifestyle continued until the 1970s, when the last of the mills closed down. Because this way of life continued for so long, some of the former millworkers still live in the Blackstone Valley. The youngest are in their mid-seventies, while most remaining mill workers are older. Within a few years, the last of the millworkers will be gone, and their stories would be lost. When working alone, I didn’t have any funding to create a completed product. That’s where Blackstone Heritage Corridor, Inc. (BHC) came in. When the COVID-19 restrictions hit, I connected with BHC to begin a summer practicum under the supervision of Volunteer Coordinator Suzanne Buchanan. After pitching the idea to her, she arranged a Zoom meeting for me to seek support for the project. An initial meeting with BHC and National Park Service staff and volunteers was highly successful, and I was given the go-ahead to build the project, thanks to funding found by BHC director Devon Kurtz. I have been working with media expert Brad Larson to put my interface over his StoryKiosk framework, along with local historian and PHNN member Marjorie Turner Hollman to create a list of interviewing questions to guide the storytellers. To find millworkers who want to tell their stories, I hope to turn to a few different sources. During the early stages of recording, as I find the best way to interview millworkers using this new technology, I will collect the stories of local community members whom I have known for most of my life. Many local historical societies are run by the very same people who once ran the mills, and they have kept in contact with their fellow workers. The Rhode Island Manufacturers Association is another resource, as they connect the industries of the past to those of the present. I’m excited to begin collecting stories from the former millworkers of the Blackstone Valley. All of the stories will be held in a database that can be made accessible to other organizations related to the Blackstone Valley, like the Museum of Work and Culture in Woonsocket, RI. Selected stories will be shared on the BHC social media, including their Facebook page, Instagram feed, and YouTube channel, along with hopefully appearing in future exhibits once restrictions are lifted. If you know anyone who worked in the mills of the Blackstone Valley or had close family that worked in the mills, feel free to send them my way! My email is [email protected]. Bio Abigail Epplett is a MA candidate in Museum Studies at Tufts University, focusing on informal education and American history. She recently completed a summer practicum with Blackstone Heritage Corridor, Inc., a non-profit organization affiliated with the Blackstone River Valley National Historic Park in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and continues to volunteer with the National Park Service. Members and invited guest writers are welcome to submit posts, which will be approved, and edited. Personal business promotion will disqualify submissions. Author attribution with brief (50 words or less) bio and headshot is required. For information, email Marjorie Turner Hollman.

|

PHNNWe are an organization of professional Personal Historians from the New England States. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed